OUTLOOK ON WESTER ROSS the website of Jeremy Fenton

Once upon a time the world was young, hot and violent. It took about a billion years from its birth 4570my (my = million years) ago for things to quieten down. By then, the surface had cooled enough for a rock crust to form on it, and volcanoes had started to create small continents from rocks such as quick-

In the region which would one day become North West Scotland, a group of these terranes formed, with basements of gneiss (called Lewisian Gneiss here); the original granite-

Meanwhile, in the Gairloch area a remarkable set of different rocks had been added to our particular terrane, about 2000my ago: the Loch Maree Group. These had been formed on an ocean floor and pulled under the gneiss by the process called subduction. They were then folded into the gneiss and metamorphosed during the 1670my episode. They include amphibolite (formerly ocean-

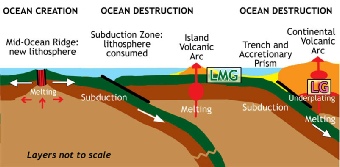

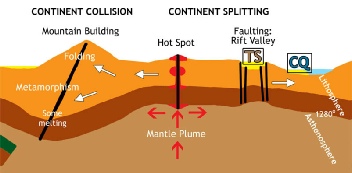

By now the process called plate tectonics was well under way. The earth's surface is made of plates, oceanic (made of basalt) and continental (made of many rocks), which move constantly. Oceanic plates are being constantly created along volcanic ridges, and destroyed by being dragged down into the depths of the earth (subduction). But the lighter continental plates, like floating islands or icebergs, are safer; they may join and divide, but they are not destroyed because they are buoyant and often have a strong basement of gneiss. When continents collide, mountain ranges are pushed up; it may take as little as 50 million years for these ranges to be eroded back down to nothing, and their remains then form layers of new rock (sedimentary).

In our area, the rocks above the gneiss were worn down until the gneiss lay on the surface, ready for the next stage. To the west a mountain range formed, which was then eroded to create a huge amount of sediment. This sediment was carried by broad rivers to be deposited on the Gneiss. Under its own weight it was compressed to form 2km-

At 1000-

Torridonian Sandstone often shows signs of its origin in rivers and shallow lakes, in a hot dry environment near the equator. You can see ripples, drying cracks, layers of pebbles, cross-

By now we were on the eastern edge of a continent called Laurentia (today’s North America). As we drifted to the South Pole and back again, much of the sandstone was eroded off. 540my ago the next rock was deposited on top of it, along the shore of the Iapetus Ocean. This was a white sandstone, formed from beach sand which was almost entirely quartz; it is called Cambrian Quartzite. Today it forms a grey-

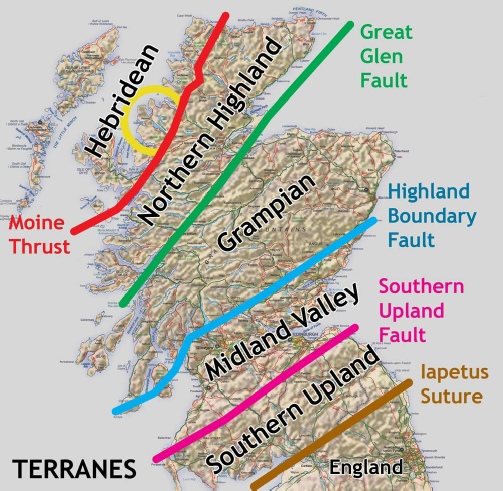

Up to now, Scotland had not been assembled; it would be put together when five small chunks of eastern Laurentia came together. These five terranes all had very different geological stories to tell, making Scotland perhaps the most geologically varied country of its size in the world. Our "Hebridean" terrane was by far the oldest. Meanwhile England belonged to a different continent, the smaller Avalonia. A third local continent was Baltica (now Scandinavia). Laurentia, Avalonia and Baltica had been joined to the supercontinent Gondwana at the South Pole, but they broke away from it and separated 580my years ago.

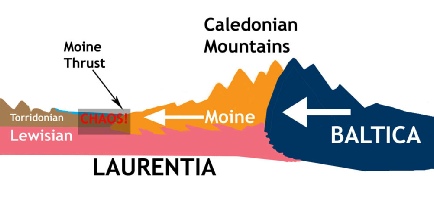

The joining of the five parts of Scotland, and England, was caused by a series of collisions between these continents. What concerns us is that 430my ago Baltica ploughed into us from the east, pushing up the Caledonian Mountains, and driving ahead of it for 50-

This movement, called the Moine Thrust, is very important in explaining the uniqueness of the geology and scenery of our area, Wester Ross. The thrust, or rather series of thrusts, stopped short of Kinlochewe, covering everything to the east with the schist but leaving our area untouched, except that today the hills near the thrust show spectacular examples of its effects; for example:

- Beinn Eighe, Beinn Liath Mhor and Sgorr Ruadh are "imbricated", with alternate slices of sandstone and quartzite: as you walk along their ridges the rock keeps changing.

- Meall a' Ghiuthais and Maol Chean-

Dearg have older sandstone tops above younger quartzite: the sandstone was pushed over the quartzite. - Beinn a' Mhuinidh (next to Slioch) has a gneiss summit above sandstone above quartzite, and a gneiss base! -

a series of thrusts pushing slabs (nappes) of rock on top of each other. - Mullach Coire mhic Fhearchair has an unexpected east ridge whose top is gneiss; the rock is very shattered thanks to its violent treatment.

At the top of Glen Docherty, after the drive west from Achnasheen, there is a viewpoint. Many drivers stop there, because the view is startling: a different world lies ahead. Wester Ross is a rugged, rocky, complex area formed by hard ancient rocks, contrasting with the greener, softer land to the east. As you drive down Glen Docherty, you are crossing the Moine Thrust.

There is a brief postscript to the story of our rocks. 250my years ago, in a desert environment, Triassic (or New Red) Sand-

At this stage our landscape had not been formed. But over the next 200 million years weathering (rock damage) and erosion (rock removal) were at work. A new super-

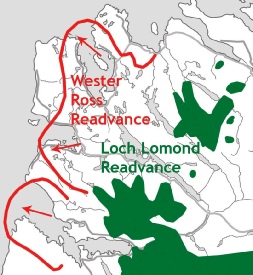

Now the final stages of creating our landscape could start. Valleys formed, often where cracks (faults) had weakened the rock. Eventually our northern drift took us into the realm of Ice Ages, and glaciers could start to carve the land, deepening the valleys and isolating the mountains. The final stages of the last Ice Age were the Wester Ross Readvance, about 16,000 years ago, and the Loch Lomond Readvance, ending 11,500 years ago; these put the finishing touches, cutting out corries, narrowing mountain ridges, laying down the sandy basis of soil, and scattering boulders and gravel over the land.

The desert left by the ice was soon covered by vegetation. Humans arrived. And they all lived happily ever after (or at least until the next Ice Age, the next inundation, the next tectonic activity, or serious climate change).

This is an attempt to summarise the geological past of Wester Ross in narrative form with minimal jargon; but it’s still not simple! For more detail and explanation, see my booklet “Wester Ross Rocks”.

Simplified geological map of our area.

Pink = Lewisian Gneiss

Green = Loch Maree Group

Brown = Sandstone

Blue = Cambrian Quartzite

Orange = Moine Schist

Typical Gneiss

Part of Scourie Dyke

Amphibolite

Sulphide Deposit

Mountain-

Where they started:

LMG = Loch Maree Group

LG = Lewisian Gneiss

TS = Torridonian Sandstone

CQ = Cambrian Quartzite

Meteorite-

Quartz veins

Water-

Cambrian Quartzite

Pipe Rock (Skolithos)

Beinn Eighe: alternate quartzite

and sandstone (imbrication).

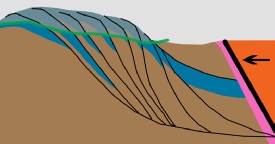

Below: how imbrication works:

before and after.

Meall a’ Ghiuthais: older sandstone above younger quartzite. Note the quartzite “bow-

Moine Schist in the river south of Kinlochewe

Glen Docherty: through the Moine Thrust to Loch Maree

Blue quartzite

Brown sandstone

Green = surface today

Triassic sandstone

Volcanic Skye: gabbro (Cuillin)

Alpine glacier

Ice-

“Knock and lochan” country typical of the Lewisian Gneiss:

small hills (Gaelic cnoc) and lochs

The biggest “pro-

The biggest rockfall in the UK below Beinn Alligin: perhaps 90 million tons

of sandstone, 4000 years ago

Knowing Gneiss

Like skerries in a sea of greenery

rock breaks the land here, shakes away

the softness of grass, splashes itself in

rags of heather, repels waves of

whins and ferns and windblown rowan.

It bursts from hiding, boasting its

solidity, its everlasting strength.

Gneiss knows its age, numbers its years

in hundreds thousands millions billions.

Gneiss shows still its birth in earth's long

heating, kneading, tearing, twisting;

shows too its slow death, worn by ages

of gneiss-

last and least the storm of upstart life ... and us.

Does gneiss ignore us, ephemeral gnats,

featherweight and fragile as we scutter by,

too taken with our niceties to notice it?

Or does it sense, this ancient creature, that here

at last is the one long promised, the Adam, the namer,

the knower, giving to all created things

existence?

Recognise the rock and make it glad.

Ice-

Gneiss landscape

Folding, 1670my

Pegmatite, 1670my

Semipelite (weathered)

BIF: magnetite, quartz

Marble

Layers of sandstone and breccia

Pebbles in sandstone

Cross-

Colourful breccia

…and conglomerate

…and basalt (Trotternish)

An obvious “erratic” left by the ice

The oldest rocks in Western Europe